A new cave diving exploration record. During an epic 7-hours dive in the Font Estramar of the Eastern Pyrenees, speleonaut Frédéric Swierczynski from Marseille reached an astonishing depth of -308m!

My journey to -308 m

By Frédéric Swierczynski

Interview by Francis Le Guen

I am below 260 meters underwater; my discomfort in my eye finally stops, and I can see clearly. I decide to make a quick assessment of my situation: I am conscious and choose to continue moving forward while laying the line. A vertical shaft appears, and I can see the gallery continuing to descend even deeper. The tunnel, made of scoriaceous rock, is vast and disappears into the darkness. I’m the first person here, alone. I drift into the blue night, with the only point of reference being the sound of my breathing roaring through the canisters of my rebreather and the motor of my DPV. I feel good, extraordinarily lucid

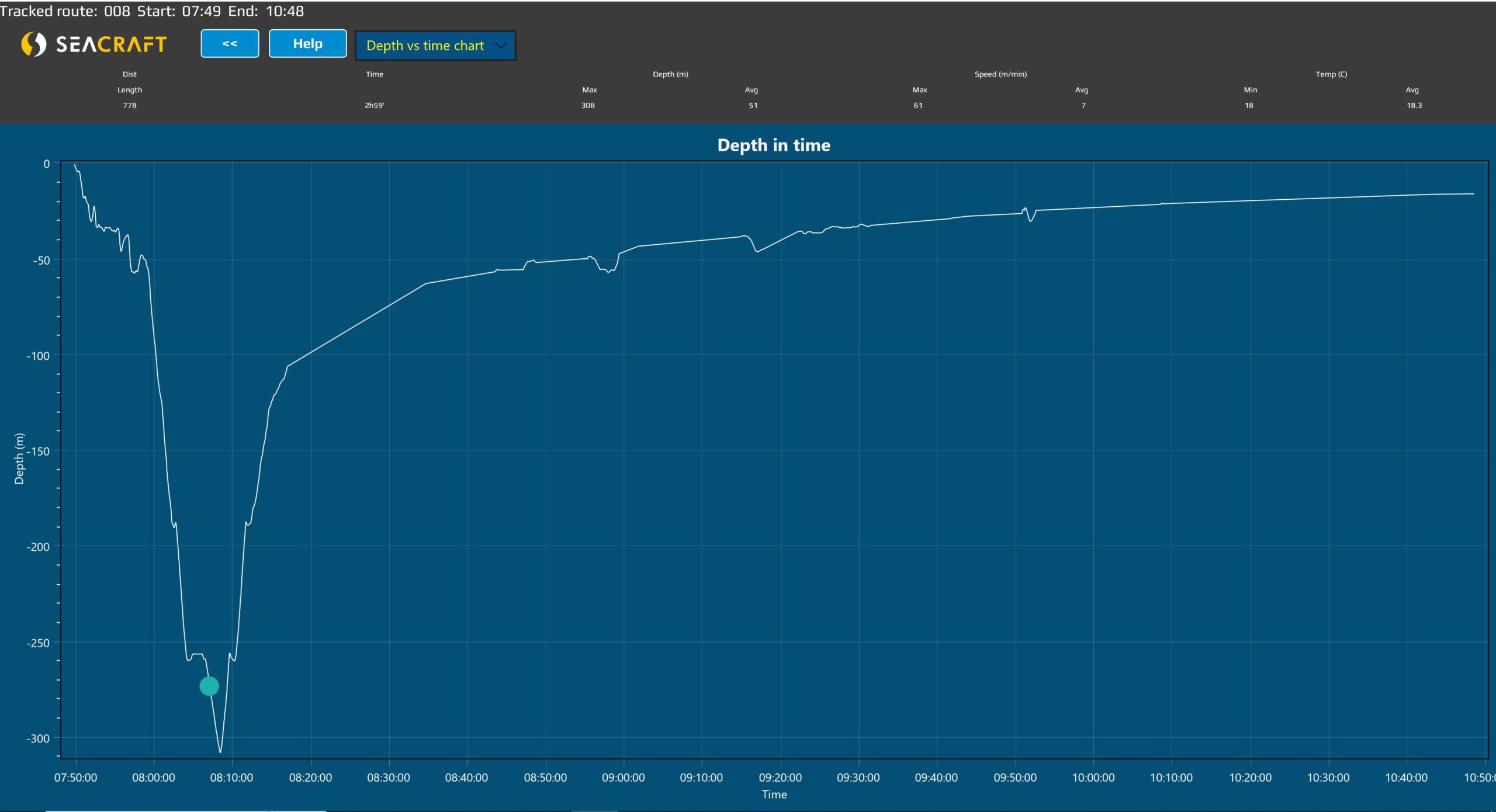

I secure the line to a carved stone; my hands tremble not only with excitement but also due to symptoms of ‘HPNS,’ the dreaded high-pressure nervous syndrome. Despite this, I continue, feeling liberated in this immense aquatic clarity. The atmosphere is otherworldly. I pass by a bed of sand, rippled by the current. Ahead and below me lies a vast and expansive chamber. Glancing at my timer: 400 minutes of decompression… Fred, it’s time to head back! I’m 50 years old, and today I’ve reached a depth of 308 meters, setting a new world record. Yet, at this moment, I haven’t fully comprehended it. I’ve never been one to base decisions solely on numbers; for me, it’s about the experience, the sensation, the feeling… something exciting.

Salses le Château – November 3, 2023 – At the edge of the Font Estramar spring – T minus 10 minutes before the start of the dive.

It’s been an almost sleepless night. I managed to grab some sleep, but my dreams lingered. The same recurring images, nothing really new. For at least two weeks, my nights have been consumed by meticulously replaying every gesture, every second of that dive. Living on credit in the deep darkness, optimizing every instrument control, visualizing myself navigating the distant gallery, relying on that precious yellow guideline…

It’s been an almost sleepless night. I managed to grab some sleep, but my dreams lingered. The same recurring images, nothing really new. For at least two weeks, my nights have been consumed by meticulously replaying every gesture, every second of that dive. Living on credit in the deep darkness, optimizing every instrument control, visualizing myself navigating the distant gallery, relying on that precious yellow guideline…

Beneath the tranquil, transparent blue surface, green algae sway, revealing the current emanating from beneath the earth. Where does this mysterious river originate?

As I prepare my equipment by the spring’s edge, attempting false cheerfulness, I engage in conversation with veteran deep divers who have come to lend their support. We reminisce about the heavy, open-circuit diving operations from just a few years ago, involving dozens of tanks and days of preparation, contrasting with how I now manage it all in just 20 minutes!

I reminisce about the past months: the endurance races in Marseille’s Calanques, hours of breathless exertion on the slopes, kilometers traversed through pine forests, scrublands, and rolling limestone scree. And then, the countless deep training dives, here in the warm waters of the Catalan country, plunging down to the -260m zone. These dives aimed to acquaint myself with the underwater topography, navigating the flooded gallery stretching over a kilometer, and perhaps to acclimatize both body and mind.

I meticulously refined my decompression curve, aiming for the most precise adjustment possible: minimizing dive time without compromising safety. I adapted my equipment in minute increments, striving to merge seamlessly with the environment, making its challenges my own. Unbeknownst to my conscious self, my body had already made the decision to venture into the unknown, beyond the -300m mark.

T 0 – Here we go!

The DPVs and rebreathers are submerged, meticulously set timers syncing with other divers joining me at the -120m decompression stops. Heated underwear, drysuit—getting help to seal it while I adjust equipment in the water basin, my body halfway submerged. Harnesses, fins, rebreathers—a ritual repeated over the past months. I cannot afford to overlook anything; it’s all going to happen in a flash. Each piece of equipment must respond instantly to my needs. The mask—a precious necessity. I rinse it, adjust it meticulously, and then I’m off.

The aquatic horizon appears blue, kissed by streaks of sunlight. A black archway reveals itself within the gray rock. I descend into the vertical shaft that follows, allowing myself to be swallowed by the night. Equalizing my ears, ensuring the drysuit fits snugly, rebreathers’ lungs emptying, the hiss of the inflators—a battle against pressure unfolds!

The DPV propels me into the submerged gallery at over fifty meters per minute. I seize the moment to glance at the rebreather displays, checking the partial pressure of the oxygen mixture I’m breathing. It’s crucial information. I can’t divert my eyes from these indicators; it’s the only way to prevent potential poisoning.

T+5 minutes – On the way…

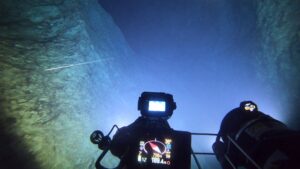

My vessel maintains a steady cruising speed, led by a Seacraft scooter ahead, towing me while another serves as a backup, secured to my back. My headlights pierce the distance as the crystal-clear water reveals passing walls. The automated control of my instruments is in place. I navigate above the guide cord installed in the main gallery, beneath the vaulted arches stained with iron and manganese oxides: hues of rust, brown, yellow ochre, deep black, and red clay. Eroded mineral structures, sharp as razors, intersect secondary galleries, and the current’s direction occasionally plays tricks on us.

My vessel maintains a steady cruising speed, led by a Seacraft scooter ahead, towing me while another serves as a backup, secured to my back. My headlights pierce the distance as the crystal-clear water reveals passing walls. The automated control of my instruments is in place. I navigate above the guide cord installed in the main gallery, beneath the vaulted arches stained with iron and manganese oxides: hues of rust, brown, yellow ochre, deep black, and red clay. Eroded mineral structures, sharp as razors, intersect secondary galleries, and the current’s direction occasionally plays tricks on us.

Font Estramar resembles a complex labyrinth of corridors and dead ends, where losing your way is not an option. I await Patrice Cabanel, following me on his double DPV. He speeds past me, diving much deeper into the expansive vertical well to capture a few videos as I continue my journey.

T+8 minutes – Jump.

Descending 60 meters. The actual dive commences. Final checks precede the big jump: activating the powerful dive lights and starting up all equipment that will encounter pressure at depth. It’s the last feasible moment before the impending darkness… I prepare myself—it’s time to jump!

T+10 minutes – Around -200…

At -100m, I meet Patrice, camera in hand, eagerly awaiting my arrival. He joins me in the descent! -150m, -170m: we accelerate! Swiftly. Perhaps too fast. Like two bikers racing on a vertical track, each trying to outpace the other… He remains close behind, but the maximum test depth of his scooters becomes critical at -180m.

I signal to halt him—I don’t want his vehicle to implode under the extreme pressure! The memory of the Finnish diver torn apart by his scooter lingers in my mind; I was there to investigate the accident at the request of French authorities. His body remains in that cavity, now his underwater tomb, buried beneath 200 meters of water. I continue my descent, the haunting echoes of crazy organ music reverberating in my head.

I signal to halt him—I don’t want his vehicle to implode under the extreme pressure! The memory of the Finnish diver torn apart by his scooter lingers in my mind; I was there to investigate the accident at the request of French authorities. His body remains in that cavity, now his underwater tomb, buried beneath 200 meters of water. I continue my descent, the haunting echoes of crazy organ music reverberating in my head.

As Patrice Cabanel recalls: “What’s just a little over halfway for Fred represents an immense leap for me. I’m at a depth of 190m, watching him sink further. It’s surreal, seeing him surpass 200m and vanish from my sight…”

T+14 minutes – Dazzled.

As I continue my descent, the rock formations become lighter, indicating a shift in geological layers—it’s as if I’m traveling back in time. I’m approaching the horizontal section of the tunnel, fluctuating between -250m and -260m—a familiar place from my numerous training visits. A round trip usually adds an extra hour to my decompression, but today, I anticipate it’ll be much longer, as I’m going deeper.

Reaching the bottom of the well at -260m, I stand up and suddenly experience an unfamiliar discomfort: a dazzling sensation. The floor of the submerged horizontal gallery appears flooded once again; it’s like an illuminated sea, shimmering with reflections. I move forward as if in a dream, feeling disoriented.

In the professional field, a compression at -300m considered ‘quick’ takes… 24 hours! However, there are challenges associated with compression in a bell or diving box, particularly the gas heating issue, which needs time to cool. Such problems aren’t faced by a scuba diver underwater. But today, this isn’t just training. The quick descent with Patrice has likely accelerated my usual speed. I may be paying the price for it now.

T+16 minutes – High Pressure Nervous Syndrome.

The discomfort dissipates as abruptly as it arrived, and my vision returns. It seems my horizontal journey to the lip of the terminal shaft has revitalized me. Ahead, a black abyss. No more lifeline! I must secure my own reel and ensure the line’s safety. My hands tremble… HPNS, it’s not uncommon. Over more than 12 years of deep dives below the -200m mark, it’s become a familiar companion, no longer surprising me.

T+? minutes – Sleepwalking.

I’ve lost track of time; I’m in a state of ecstasy. The moment I’ve waited for, perhaps more than 6 months—or is it 20 years?—has finally arrived. My scooter’s at a low speed, the yellow line unwinding steadily, and my body’s ‘trim’ is perfect. Balance and positioning in this liquid realm are crucial for survival; they minimize physical exertion and, consequently, metabolism. With wide-open eyes, I absorb the unknown surroundings passing by me; the receding blue horizon guides my progress, gestures, and decisions. Now, it’s the exploration itself that drives my dive. I glide into an increasingly expansive chamber, drawing me in—toward my destiny.

Visibility extends beyond 25 meters! My sight loses itself in the blue transparency that transitions into blackness. It’s majestic, truly majestic.

I keep a vigilant eye on my line, ensuring it doesn’t snag in the narrow sections of the gallery. I leverage my optimal mental state to capture these envisioned magical moments—moments that are now mine. Another line splits on a sharp rock beneath me, and my computer alerts me: 400 minutes of decompression already! It feels too brief; I yearn to continue. It’s a struggle to break free from the allure of unexplored depths. I hasten. Every passing second is crucial at these depths. I decide to secure my reel, leaving it to mark my terminus. A nod to Krzysztof Starnawski, another deep diver, who had abandoned a reel at the bottom of the magnificent Cetina spring in Croatia—an artifact I had retrieved during my initial dive there.

I propel toward the distant surface. My ascent is swift. Eager to detach from the abyss and commence decompression. It’s happening way too fast, and the cost will be high, though I’m unaware of that yet…

T+28 minutes – Junction!

Arriving early at the first stage at -130m, I commence following the deco stops. It’s at -90m where Bruno, the support diver, finally joins me. Finally, I have access to all my measuring instruments. And there, I discover the incredible depth I’ve reached: -308m! Typically, during these deep dives, I initially monitor my condition, followed by the partial pressure of oxygen, the ‘run time’—the diving time—and the expected duration of the stops. Depth becomes secondary… I don’t fixate on it. If my body signals approval, I proceed. There wasn’t any distress; it was the constraints of decompression time that compelled me to turn back.

T+40 minutes – I can’t breathe anymore!

We’re swimming towards the -80m level when I suddenly encounter extreme difficulty breathing—my rib cage feels constricted! My lungs seem blocked, my upper body trapped. Gas poisoning? Swiftly, I switch the rebreather tip, yet to no avail. It’s not gas toxicity; the issue lies elsewhere. Faced with this unknown, fear lingers, but panic is unattainable. I must rely on my wisdom and experience… I try ‘stomach breathing,’ as in training. Labored. Like sipping through a straw. But even with limited ventilated volume, it suffices. Minutes tick by… Bruno remains by my side, watching over me for four hours.

Worse still: a sharp pain grips my back. Alongside breathing difficulties, an oppressive sensation prevails—as if my suit is being crushed, the metal plate of my harness weighing tons. This ordeal extends for over an hour. It’s only upon reaching the 30-meter mark that the grip eases, and I finally experience liberation. I inhale. I am alive. I remember…

During the debrief with Bernard Gardette, director of deep dives and extreme environments at Comex—responsible for Théo Mavrostomos’ legendary -701m dive—I learn that the visual illuminations I experienced are symptoms of HPNS. Tremors are more common. The spectrum of detrimental effects from neurological damage due to pressurized helium remains understudied. Reports mention vomiting issues. Thankfully, I escaped that underwater. These are irksome but reversible physical conditions, leaving the intellect unscathed.

However, the respiratory oppression appears linked to a massive helium outgassing from my too rapid ascent. Circulating bubbles that I gradually eliminated from my lungs, yet symptoms of spinal cord and kidney injury persist. The spinal cord—a risk of permanent paralysis…

Indeed, our computers are programmed to warn against rapid ascent. However, I’ve grown accustomed to my personal calculations and procedures, ignoring these warning bells, letting them ring out. Who’s the boss here? I’ve grown accustomed to their persistent tunes, like a man at home ignoring his wife’s shouts…

Indeed, our computers are programmed to warn against rapid ascent. However, I’ve grown accustomed to my personal calculations and procedures, ignoring these warning bells, letting them ring out. Who’s the boss here? I’ve grown accustomed to their persistent tunes, like a man at home ignoring his wife’s shouts…

Gardette confirms that we can ascend rapidly from -300m to -200m, but it’s crucial to slow down before the first significant deco stop! Valuable information that I’ll heed for my upcoming dive in the terminal well of the Mescla cave in the Var gorges.

T+120 minutes – The motionless journey.

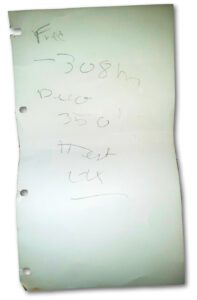

Franck joins us at a depth of 50m. It’s time to jot down a message, a simple wet sheet of paper destined for other divers higher up and the surface. It reads: ‘Fred -308m all is OK’…

Franck joins us at a depth of 50m. It’s time to jot down a message, a simple wet sheet of paper destined for other divers higher up and the surface. It reads: ‘Fred -308m all is OK’…

Many hours still separate me from the surface. I’m doubly confined: in the flooded gallery and by this physiological limit preventing me from directly ascending, risking a severe or even fatal decompression accident.

I float, entering a ‘degraded phase,’ almost in a drowsy state. It’s about aligning my physiology to its vital minimum, merging with water effortlessly. Listening to time stretch and dreaming of what lies beyond…

T+200 minutes – Leak…

As I approach the bottom of the exit shaft, daylight becomes visible from afar, urging me to scream. But at the -12m stop, a new alert emerges: a distinct sensation of fluid loss, from hip to foot. It feels as though I’ve urinated in my drysuit, an eerily realistic sensation sparking doubts. A slight movement reassures me—my leg functions properly, and I remain dry. However, the ‘leak’ persists, an unending ‘bladder’ sensation. Gardette later attributes this to ‘skin sensations,’ a decompression-related phenomenon sans gravity.

9m. The bell! I could conclude my decompression here, in dry comfort with legs in the water. Yet, I opt to forgo it. Changing the setup—a complete shift of environment, positioning, and potentially obstructed blood circulation—poses risks. So, I remain horizontal, weightless, in a daze, choosing optimal decompression. I float serenely, a weightless entity within my rocky vessel, content and almost at ease.

Adjusting my heating: despite the relatively warm slightly brackish water at 18/19°C, the risk of cold remains due to immobility and stronger currents in this convergence point of the fountain’s galleries.

Life teems here! Curious eels navigate among my equipment, while silver mullets dance in the sun. At minus 6 meters, filamentous algae drape and twist like theater curtains, mingling with lignite roots and reed beds.

Time for a snack—my Catalan country apricot compote bottles provide an unexpected energy boost. A realization strikes: dehydration likely plagues me, a negative factor for decompression. I’ll need to remember to hydrate more during future attempts.

Nearly 7 hours underwater, helium gradually dissipating from my body, the surface is tantalizingly close. I observe it, a reflective mirror above me. With humility, I reflect on this new milestone in exploration—a paradigm shift challenging established beliefs, a leap forward for the entire community.

Our exploration endeavors always build upon past achievements. I think back to our pioneering elders, those who steadily dismantled psychological barriers. This marks a new frontier, a plank thrown into the swamp, paving the way for further progress. The great speleonauts all took this leap. It was time for me to do the same. I feel a sense of pride in these moments of pure beauty, in claiming a few dozen meters from the unknown, and in being able to recount this tale.

T+419 minutes – Surface!

I break the surface, lowering my mask and hood. There are splashes, silver droplets, laughter—sounds from the outside world; the smiles of friends. And the unmistakable scent of life…

Acknowledgments – Partners

Comex SAS – Phymarex – Beuchat – Seacraft – Isotta Housings – MPS Technology – Plongimage – Ursuit – Aventure Verticale – Eurodifroid – Xdeep – Custom Diving Systems – Plongee.ch – Damian Jakubik – Witold Hoffmann – Alpha Requalification – Santi Diving – Georges Ruggeri – Olivier Bertieaux – Elisa Isotta – Manlio Pagotto – Nina Katia Ferro – Lucie Šmejkalová – Komninos Boutaras – Jakub Slama – Mathieu Coulange – Bernard Gardette – Olivier Isler – Cyril Brants – Richard Harris – Nuno Gomes – Krzysztof Starnawski – Luigi Casati – Laurent Miroult – Alexandre Legrix – Severi Rouvali

Deeper…

My equipment

Throughout my dives, I have selected and tested a whole range of equipment from the best europeans manufacturers. Above all, able to function and withstand the significant pressures of the depths where I operate (>300 m).

Thermal insulation

Diving drysuit Ursuit (Finland).

Heated underwear Santi (Poland). I regulate the heat provided by the Seacraft DPV batteries.

Buoyancy

Thanks to the harness XDeep (Poland) and the “Sidemount” configuration of my rebreathers, I obtain perfect trim with a minimum of ballast. I dive without a buoy, using only the inflation of the drysuit for balancing. If unfortunately one of my rebreathers were flooded, making my weight negative and dangerous, I would just have to unhook it and leave it there.

Breathing

Rebreathers

2 closed circuit rebreathers (Czechia) worn sidemount. I breathe on the main (degraded), fixed on the left side, while regularly testing the backup (redundancy) on the right side. The latter is more flexible when breathing due to the position of the inspiratory lung, closer to the body. Filters modified in size, each allowing a duration of 9 hours in C02 purification. With an autonomy of 9/10 hours per rebreather.

Gaz

Trimix 4/89 mixture (Oxygen, Helium, Nitrogen).

Tanks

Each rebreather included 2 x 2 liter tanks (pure oxygen and diluent) to which I added a 2 liter tank of compressed air at 374 bars for inflating the suit and another 2 liter tank of 4/89 diluent (off board) to compensate the too low autonomy of the big deep rebreather. Totally 6 tanks.

Deco

2 computers (Czechia), modified Buhlmann algorithms, independent and supportive of each rebreather.

Propulsion

2 scooters Seacraft Ghost (Poland). Pressure test >300 m. Multi-speed. More than 10 hours of operation for 30 km of autonomy. Also serves as a battery for heating. Supports main lighting and an inertial measurement console. Designed to operate coupled, I separated them, keeping one as a backup fixed behind me, so that I could have one hand free when navigating.

Vision

2 main lights of 50,000 lumens each attached to the front of the scooter. I am the designer and manufacturer of them with our brand Callisto (France).

1 front Phaeton (Greece) attached to the helmet. 10 hours of autonomy at 20W adjustable to be able to illuminate the near field, the hands during reel maneuvers (French technique)…

1 light Tillytec (Germany) fixed on the arm: 2 h at 4200 lumens.

Images and datas

Navigation console ENC 3 Seacraft (Poland). It is an inertial unit which allows the position in space to be recorded, coupled with a “loch top” as in sailing, a small propeller allowing the displacement to be recorded.

Camera housing Isotta (Italy) worn on the head.

Miscellaneous

Several tools and cutters.

Harness and buckles.

Fins, emergency equipment (mask, etc.), lighting and comfort.

Decompression

Individual deco bell installed at – 9 m. Scalable up to – 6 m. Fixed by cables on the bottom with ballast or bolts (expansion bolts). Sitting position, legs in the water. Homemade. 2×4 hours of oxygen autonomy per open circuit cylinders.

The configuration for Font Estramar: perfect trim with two sidemount rebreathers, a main DPV and another towed emergency DPV.

Gas mixtures and consumption.

Mix type

I use Trimix. For this dive, 4/89 that I prepare myself. Why Trimix rather than Heliox? I did some tests but the Trimix is ??much more “comfortable”. In addition, the presence of nitrogen in the mixture would limit SNHP (high pressure nervous syndrome) thanks to the narcotic effect of nitrogen. I use a low percentage in mixtures (between 7 and 10%) to avoid narcosis and limit nitrogen saturation. For this dive, the compressed air nitrogen equivalence corresponded to – 30 m. The isothermal performance is also better.

What about the use of Hydrogen as a diluent in deep diving? The Australian Richard Harris successfully tested it while exploring the Pearse River in New Zealand. It’s innovative and maybe it’s the future? We are indeed “test divers”. But there is not enough perspective on decompression. According to Bernard Gardette of Comex, who had successfully completed the first very deep dives with this gas, the decompression algorithms for Hydrogen are modeled on those used for Helium and this would therefore bring nothing in terms of diving time.

Above all, there is a serious safety problem: mixed with Oxygen, Hydrogen risks reacting explosively to produce… water! It’s an unstable mixture that requires rigorous industrial procedures: You can’t do that in your garden…

Making of mixtures

Starting from B50 industrial bottles of pure gas with the usual procedures. First I transfer the Oxygen, then the Helium then I add air. At all times I check the O2 level with several instruments and my spreadsheets. Next comes the overpressure procedure to fill the diving tanks with a booster MPS Technology 380 bars, an Italian company that has been following me for a long time.

Gas recycling and decarbonization

2 sidemount rebreathers with 3 kg “Sofnolime” filters. I had to change the size of the original filters to much larger models because of the depths reached. Otherwise, the gas risks not having time to travel through the loop correctly: I risk breathing unfiltered gas and getting CO2 poisoning! I was inspired by what the US military had developed for their dives beyond 200 m. Comex safety rebreathers too… With of course implications in terms of respiratory comfort and weighing. I had to acclimatize myself and adapt my technique accordingly.

Note that the descent is so rapid that I directly breathe the 4/89 that I inject. The recycler then functions like a regulator: the gas does not really have time to circulate in the loop.

Oxygen Control

These are electronic rebreathers but deactivated: During the dive, I manually control the partial pressure of Oxygen constantly. I am more “oxygenated” than in the open air but I chose, unlike many, to dive with a very low oxygen level, even at the stops (pp O2 < 1.6). Above all, I fear hyperoxia. On the computer I can read the potential toxicity of the mixture. Depending on this, I inject or not the diluent or the Oxygen. It’s like a stab inflator, very practical: Right Oxy, left Mix.

Decompression

The computers work with traditional Bulhman algorithms. Connected to the rebreather, they monitor the gas I breathe in real time. And calculate a theoretical decompression from the depth of -50 where the countdown begins for this kind of cave profile. To reduce decompression times, in addition to personal procedures based on my experience and my physiology, I adopted a Gradient Factor of 80/80 which is quite committed. I am indeed close to the maximum desaturation curve (at 80%). Usually we follow a GF of 50/80… Following the findings of this last dive and to prepare for future attempts, Bernard Gardette also sent me new curves adapted to my physiology.

Consumption

As can be seen in the various data tables, during this 7 hour dive to -308 m, I only consumed 850 liters of Trimix 4/89 diluent and 486 liters of pure oxygen. Or an average of 0.4 l/min of Oxygen, including the numerous rinses. An extremely low metabolism…

Physical and mental preparation for this type of diving

Over the course of our attempts, we gradually abandoned the notion of “mixed redundancy” by transporting “bail-out” bottles in an open circuit. It’s useless at these depths because it’s too heavy! In an open circuit, for this type of diving, it would have been necessary to carry 25 to 35 kg of various gases, the equivalent of 10 bottles of 20 l to 200 b for a weight of more than 200 kg… In addition, a classic regulator does not work properly at these depths: The required flow rates are far too high.

Which means that it is necessary to develop a psychological adaptation to the potential risks of breakdown on the main rebreather. Hence the use of a second redundant recycler. We therefore completely switched from open circuit technique to closed circuit technique. Which surprises all divers of the older generation, accustomed to “assisted” breathing. Indeed, the regulators, without us being aware of it, are very flexible when inhaling, which triggers an influx of gas at positive pressure. With rebreathers it’s different: It’s our lungs that decide and it takes both physical and psychological training to be able to ventilate effectively. We must control our breathing rhythms, our consumption, our metabolism. And above all, do not allow yourself to be drawn into the effort zone, otherwise you will experience uncontrollable and often fatal shortness of breath. You have to acquire the strength to ventilate yourself for a long time. I have experience diving for more than 15 hours with this type of mixture and equipment.

My goal is to be as light as possible. The most hydrodynamic. To get to the point. To be able to progress underwater quickly and without excessive and unnecessary fatigue. In full possession of my means without superfluous accessories that could influence my psychological state. So I gave up the pressure gauges on my tanks as I am so fine-tuned to knowledge acquired during my training and development dives. I know exactly what I am consuming. A kind of “alpine technique” adapted to deep sump exploration…

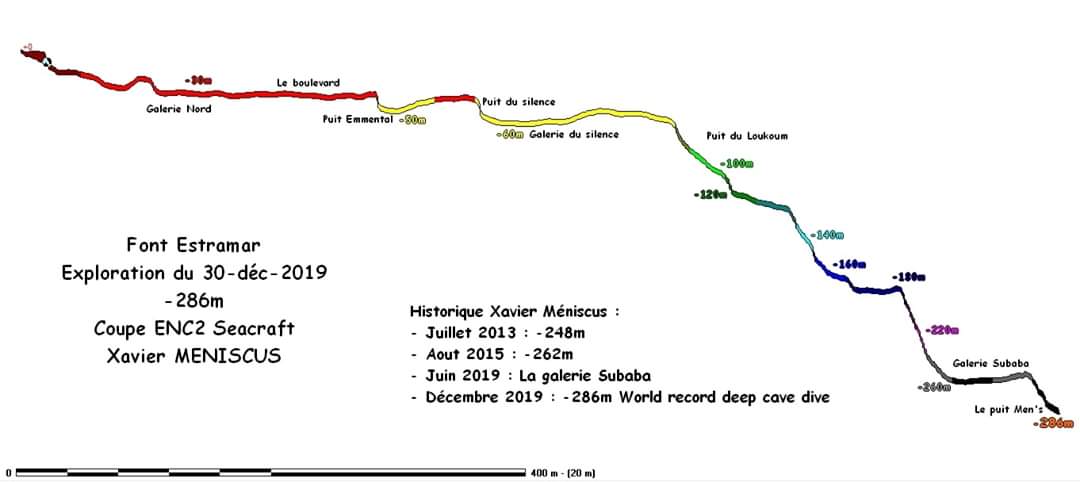

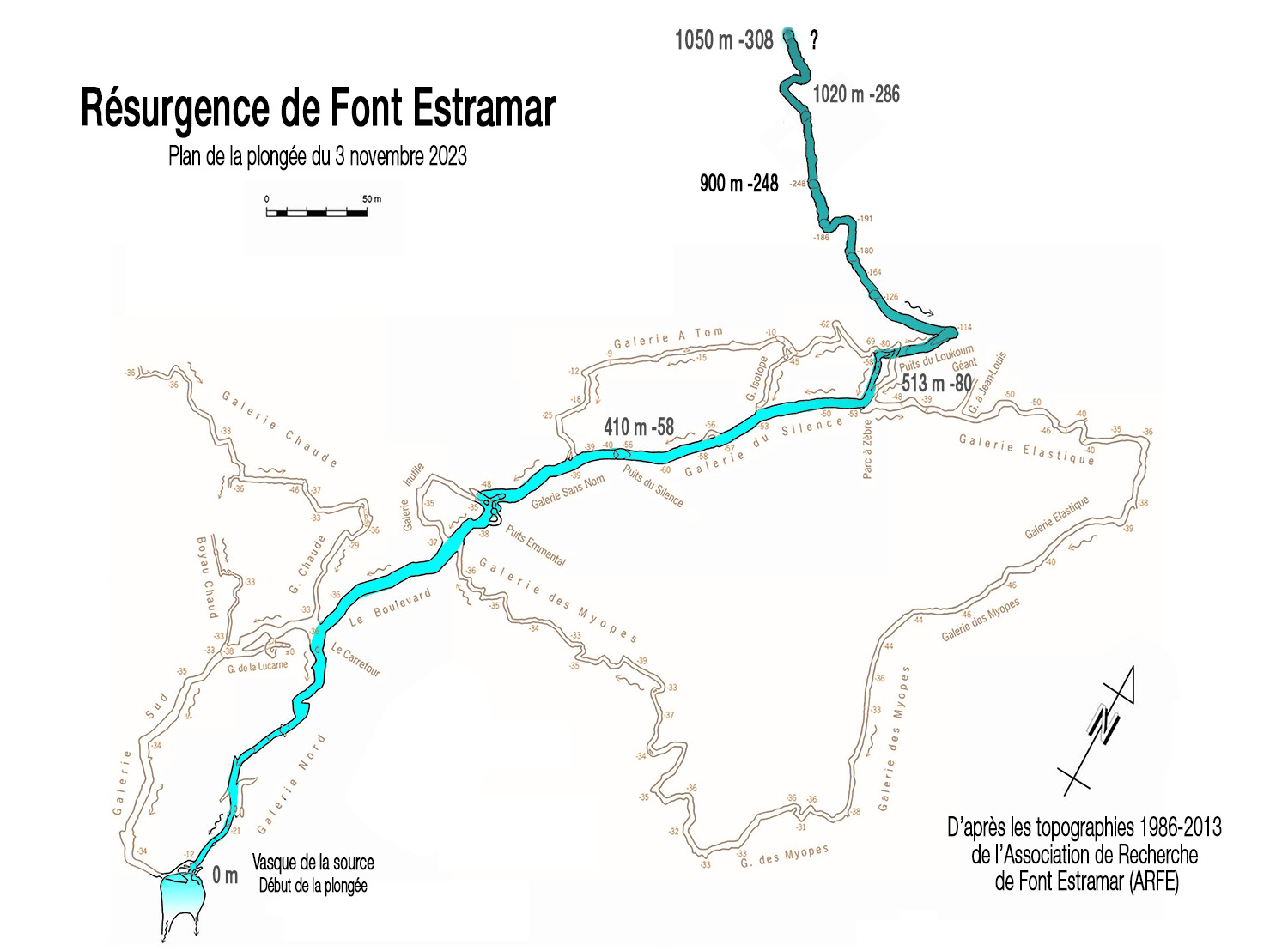

L’historique des explorations à Font Estramar.

De Cousteau à Swierczynski…

It was on the initiative of Professor Petit, Director of the Arago Laboratory in Banyuls-sur-Mer that on August 27, 1949, two officers of the 11th BPC (Shock Parachute Battalion): Lieutenant Dupas and Lieutenant George, dived into the abyss, equipped with the Cousteau-Gagnan autonomous diving apparatus. They dove through an entrance in the form of a porch about four meters below the surface, at the very foot of the cliff which overlooks the basin. From there, they progress into a vertical shaft approximately six meters high, opening into a large, totally submerged room – 14 meters from where two opposing galleries appear to branch off, one towards the south and the other towards the north. Noting that these galleries continue to sink inexorably into the mountain, the divers prefer not to explore further and decide to go back up for lack of more suitable equipment.

Followed by the expeditions carried out in 1951 by Cousteau, Tazieff and other great divers… Several secondary galleries were explored around the main conduit. The depth reached in 1955 was 50 meters, the techniques of the time not allowing it to go any lower.

In the 1970s, Claude Touloumdjian explored a total of 850 meters of galleries in several branches of the network. In 1981, Francis Le Guen advanced in the main conduit to the Well of Silence (410 m) and explored it down to -58 m.

In 1991, the ARFE (Research Association of Font Estramar) was created and the depth of 164 m was reached on August 15, 1997 by the Swiss Cyrille Brandt. Pascal Bernabé continued to ?184 m on June 4, 2006. Jordi Yherla, a Catalan diver, descended to ?191 m without finding a continuation of the sump, in July 2013.

On August 16, 2013, Xavier Méniscus, equipped with a double rebreather and helped by a large international team, continued the exploration of the cavity in the giant Loukoum well located 513 meters from the entrance, to a depth of ?248 meters (900 m from the start), bringing the development of the cavity to approximately 2,900 meters.

In July 2015, the same diver, with the help of around fifteen team members, pushed back the exploration by around thirty meters to a depth of ?262 meters.

In June 2019, Xavier Méniscus continued his exploration over a distance of 50 m horizontally to a depth of 262 meters to reach the lip of a vertical well.

After these three explorations, on December 30, 2019 Xavier Méniscus descended to ?286 meters in the bowels of Font Estramar, at a distance of 1,020 m from the entrance.

On November 3, 2023, Marseille diver Frédéric Swierczynski reached the depth of ?308 meters, a new world record, during a 6.59 hours dive. Stopping in front of the void after pulling 70 meters of line…

On January 7, 2024 Xavier Méniscus extends the gallery to – 312 m. Stop on nothing…

A cursed spring?

Due to numerous accidents, Font Estramar has a very bad reputation as an “accident-prone” cavity. Already in July 1955, during a television shoot with Haroun Tazieff, diver Jean-Claude Guiter lost his way in an annex of the south gallery and died there. A plaque on the cliff commemorates this death which will mark the spirits. This fatal accident justified a temporary ban on diving. The diver not having been found, the portion of the gallery where his body was supposed to rest was blocked. It was only in 1958 that his body was seen by André Bonneau, stuck in a chimney.

Another Czech diver died in Font Estramar in May 2008. On this occasion, the source gained its sinister reputation as a “killer sinkhole” when this was not the case, in fact. A labyrinthine maze, certainly, and deep but no more dangerous than many lesser known, and therefore less frequented, drowned caves. This resurgence is the only site in the area, so more divers go there. But there are more people dying on the beaches, or in the mountains, than here… The problem is that it’s unknown. Exploratory cave diving is a specialized discipline, which requires specific and rigorous training and techniques under penalty of death.

As Frédéric reminds us: “It is a shame that the Pyrénées-Orientales does not do like other French departments. The Lot, for example, is the number one destination in Europe and attracts divers from all over the world; an incredible economic windfall. The department took the lead: they did everything necessary to welcome the divers. It is time for things to be done the same way in Font Estramar.”

But the popularity of this Catalan source only continues to grow and the black series continues. On May 24, 2012, a specialist of the place, the Gruissanais Jean-Luc Armengaud lost his life there. We also recorded, on January 23, 2016, the death of a Sète diver in his fifties, then on June 10, 2017 the death of a 44-year-old Finn whose body was found far beyond – 200 m by Frédéric Swierczynski. Belgian stuntman Marc Sluszny in turn disappeared in a diving accident on June 28, 2018. The following July 9, Laurent Rouchette, a cave diver from Spéléo Secours Français, died during the search for the body. Finally, on July 19, 2023, an experienced diver from Puy-de-Dôme, aged 63, lost his life while returning to the surface.

The team

Left to right : Ugo Tonolini, Bruno Gaidan, Yvan Dricot, Michel Ruiz, Frédéric Swierczynski, Franck Gentili, Christian Deit. Not in the frame : Christophe Imbernon, Patrice Cabanel.

Christian Deit

55 years old. Diving leader. Caving Rescue technical manager. Bell management. A regular here, he is “The Font Estramar’s man”. He also oversaw Pascal Barnabé’s dive to -330 m in the sea.

Frédéric Swierczynski

50 years old, push diver.

Bruno Gaidan

65 years old, deep decompression support diver. 4 hours of diving from -130 m to -9 m.

Frank Gentili

54 years old. Deep decompression support from – 130 m to – 50 m. 2h30 diving.

Patrice Cabanel

30 years old, assistance diver, up to -190m. Video shots. Assembly and installation of the bell.

Ugo Tonolini

30 years old. Bell assembly. Decompression support at – 6m.

And the “Catalan team”, the local divers.

Yvan Dricot

60 years old. Logistics and good humor.

Michael Ruiz

60 years old. Support diver. Fitting the decompression bell. Logistics.

Christophe Imbernon

30 years old, support diver. Preparatory dives. Logistics. Shooting.

From + 5870 m to – 308 m: Fred, the amphibious explorer.

Speleonaut explorer. I Live in Marseille – France. I am 50 years old. Mechanical engineer. Trimix, Cave and Rebreathers Instructor. Diver since the age of 12. First solo Trimix dive at -120 m at the age of 18. Began using the rebreather in 2000.

October 1994

Font Del Truffe (Lot – France). Longest “multi-sump” dive: 21 hours.

November 1999

Saint Sauveur (Lot – France). Main gallery explored up to – 98m.

May 2016

Port Miou (Calanques of Marseille). New deep gallery was discovered in the “terminal” well, 1600 m from the entrance. + 140 m.

August 2016

Mescla Cave (Gorges du Var – Alpes Maritimes). Exploration of sump no. 3 down to -267 m.

May 2017

Crveno jezero (Red Lake – Croatia). 3rd widest karst chasm in the world, explored to the bottom at -240 m during a 180-minute dive.

May 2019

Ojos del Salado Lake (Argentina). World record for altitude diving at 5870 m.

August 2019

Miljacka – Cetina Glavas & Gospodska (Balkans). Underground post siphon camp. More than a kilometer of firsts.

September 2019

Harasib (Namibia). Deep dives (>100 m) and scientific work to the bottom of a karst chasm of more than 120 meters.

November 2023

World depth record at Font Estramar in France: -308 m.

Speleometry

The 15 deepest cave dives in the world (human explorations).

| Font d’Estramar | France | -312 m

-308 m |

Xavier Meniscus

Frédéric Swierczynski |

| Boesmansgat | South Africa | -283 m | Nuño Gomez |

| Zacatón | Mexico | -282 m | Jim Bowden |

| Tianchuang | China | -277 m | Han Ting † |

| Hranická propast | Czech Republic | -265 m | Krzysztof Starnawski |

| Nacimiento del Rio Mante |

Mexico | -264 m | Sheck Exley † |

| Fontaine de Vaucluse | France | -250 m | Pascal Barnabé |

| Viroit cave | Albania | -278 m | Krzysztof Starnawski |

| Lago Azul | Brazil | -274 m | Gilberto Menezes de Oliveira |

| Grotte de la Mescla | France | -267 m | Frédéric Swierczynski |

| Vrelo cave | Macedonia | -246 m | Luigi Casati |

| Crveno jezero | Croatia | -240 m | Frédéric Swierczynski |

| Goul de la Tannerie | France | -240 m | Xavier Meniscus |

| Sra Keow cave | Thailand | -240 m | Ben Reymenants & Cedric Verdier |

| Port Miou | France | -233 m | Xavier Meniscus |

† : deceased during attempt

The deepest drowned chasms in the world (exploration by soundings).

| Hranická propast | Czech Republic | -404 m |

| Pozzo del Merro | Italy | -392 m |

| Nacimiento del Rio Mante | Mexico | -329 m |

| Zacatón | Mexico | -319 m |

| Fontaine de Vaucluse | France | -315 m |

| Trou du dragon | China | -300 m |

| Taam Ja’ | Mexico | -274 m |

| Goluboe Ozero | Russia | -258 m |

The hydrogeology of Font Estramar

Font Estramar (or Rigole’s spring) takes its name from “Font Extrema”, in reference to its location at the extreme limit of the territory of the commune of Salses-le-Château (Oriental Pyrenees). It springs out at the foot of a small cliff, at the edge of the highway. An escarpment of tectonic origin, on the edge of a plateau nearly 200 m high, in massive limestones of Urgonian (Barremo-Aptian) facies.

Font Estramar (or Rigole’s spring) takes its name from “Font Extrema”, in reference to its location at the extreme limit of the territory of the commune of Salses-le-Château (Oriental Pyrenees). It springs out at the foot of a small cliff, at the edge of the highway. An escarpment of tectonic origin, on the edge of a plateau nearly 200 m high, in massive limestones of Urgonian (Barremo-Aptian) facies.

It drains jointly with Font Dame the karst system of Corbières d’Opoul and the Bas-Agly syncline and receives the losses from the Agly and Verdouble rivers. It constitutes the main supply of fresh water to the Salses-Leucate pond. The karst system is also connected with the Plio-Quaternary aquifer, an important water resource for the Perpignan region. The flow of the resurgence is used downstream of the basin by a fish farm before reaching the sea.

Font-Dame is a sub-lacustrine source, formed by eight emissive cracks hidden by a floating phragmites marsh (exploited reed bed). Both are important Vauclusian springs with a low flow rate of 1.5 m3/s for Font Estramar and 2 m3/s for Font-Dame. Other springs mark the same tectonic contact: the temporary exsurgence of the Malpas, and emergences through the alluvium, in the Salses plain. The whole represents the outlets of the karst hydrosystem of the south-eastern Corbières.

The water is slightly brackish, probably due to the intrusion of deep salty wedges coming from the Leucate pond and the sea. Indeed, in the Upper Miocene, during the “Messinian crisis”, there are more than 5 million years ago, the evaporation and regression of the Mediterranean Sea to a depth of more than 1000 m led to strong karstification below current sea level (at -300 / -400 m). Constant temperature throughout the year: 17.8°C.

Add-ons

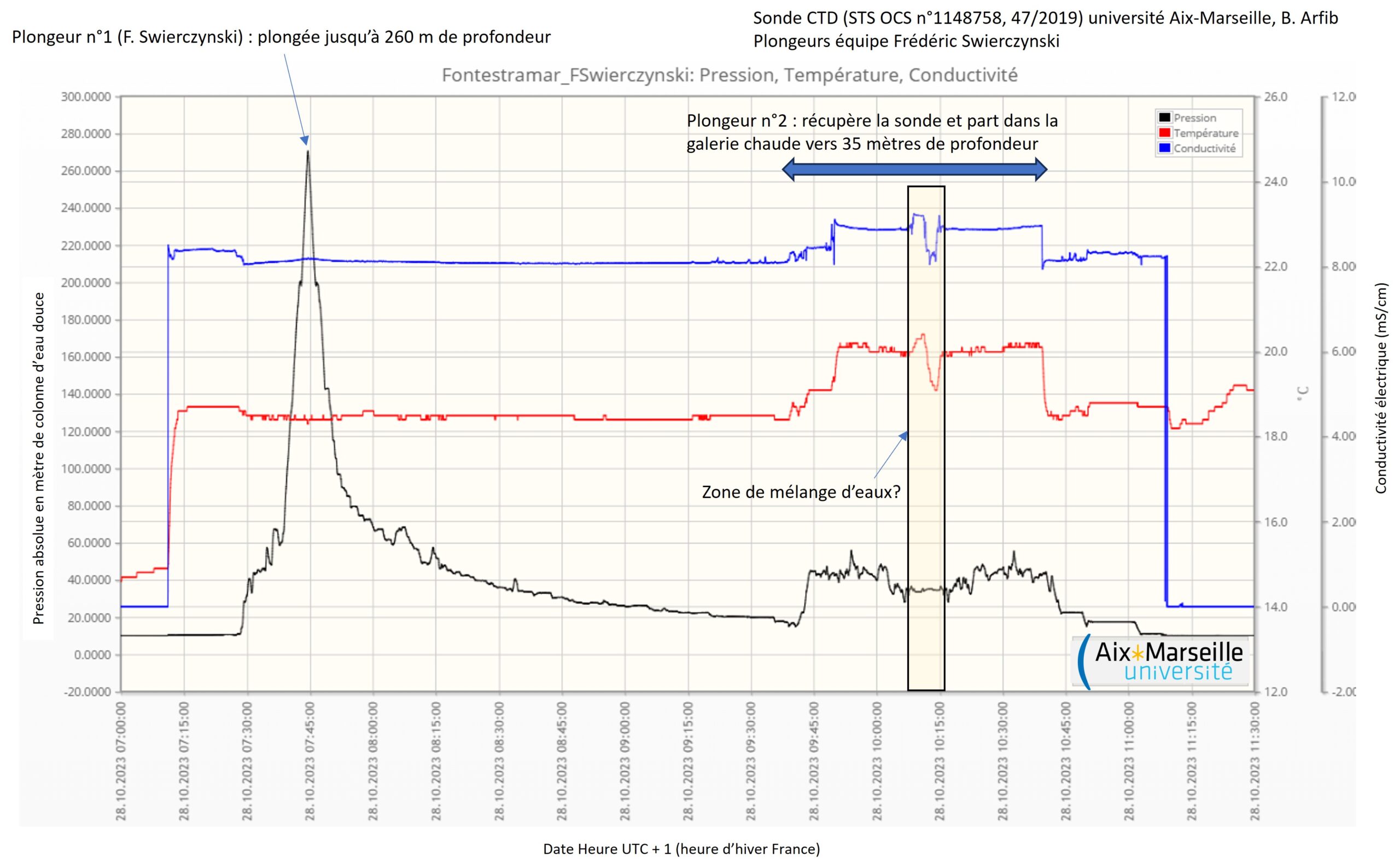

Salinity measurements of Font Estramar by Bruno Arfib – Aix-Marseille University. Diving curve of 10/28/23, recorded by the CTD probe.

« We can see quite clearly that the water in the annex gallery located around -35m is warmer and saltier. On the deep gallery, the salinity and temperature remain constant, showing no different water inflow. water is much less salty than in Port-Miou, but warmer »…

Hydrogeology summup of the spring & karsteau site.

Croatia, Namibia, Sardinia, Argentina, France, Malta, Cape Verde, Italy, Botswana… Other training sessions, premieres and expeditions by Fred to discover on: UWX.fr.

0 commentaires